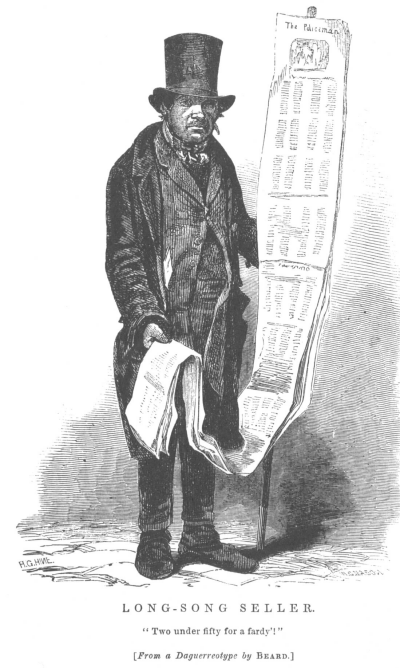

The Flying Stationers are divisible into four classes - the running and the standing patterers, the long-song sellers, the song-book dealers, and the ballad-singers. Besides these, there are others who can turn their hands to any one of the different branches of the calling, and are termed general paper-sellers. The whole class are called "paper workers." There are several printers at the east and west end of London who are generally engaged in supplying the paper workers. The principal of these printers and publishers are Mrs. Ryall (late Jemmy Catnach), Miss Hodges (late Tommy Pitt, of the toy and marble warehouse), G. Birt, Little Jack Powell (formerly of Lloyd's), Jim Paul (from Catnach's), and Good, of Clerkenwell. The leading man in the "paper trade was the late "Jemmy Catnach," who is said to have amassed upwards of £10,000 in the business. He is reported to have made the greater part of this sum during the trial of Queen Caroline, by the sale of whole-sheet "papers," descriptive of the trial, and embellished with "splendid illustrations." The next to Catnach stood Pitt, of the noted toy and marble warehouse. These two parties were the Colburn and Bentley of the "paper" trade. In connection with these printers and publishers are a certain number of flying stationers, ready to publish by word of mouth anything that they may produce. These parties are technically called "the school," and are "at the Dials" altogether from 80 to 100 in number. The running patterers are those that describe the contents of their papers as they go. They seldom or ever stand still, and generally visit a neighbourhood in bands of two or three at a time. The more noise they make, they say, the better the "papers" sell. They usually deal in murders, seductions, crim. cons., explosions, alarming accidents, assassinations, deaths of public characters, duels, and love-letters. The standing patterers are men who remain in one place - until removed by the police - and who endeavour to attract attention to their papers, either by means of a board with pictures daubed upon it, descriptive of the contents of what they sell, or else by gathering a crowd round about them, and giving a lively or horrible description of the papers or books they are "working." Some of this class give street recitations or dialogues. The long-song sellers, who form another class, are those who parade the streets with three yards of new and popular songs for a penny. The songs are generally fixed to the top of a long pole, and the party cries the different titles as he goes. This part of "the profession" is confined solely to the summer; the hands in winter usually take to the sale of song-books instead, it being impossible to exhibit "the three yards" in wet weather. The last class are ballad singers, who perambulate the streets, singing the songs they sell. Included in these classes are several well-known London characters. These parties are chiefly what are called "death-hunters," from whom you may always expect a "full, true, and particular account" of the last "diabolical murder." These full, true, and particular accounts are either real or fictitious tragedies. The fictitious ones are called "cocks," and usually kept stereotyped.

The most popular of these are the murder at Chigwell-row - "that's a trump," says my informant, "to this present day. Why, I'd go out now, sir, with a dozen of Chigwell-rows, and earn my supper in half an hour off of 'em. The murder of Sarah Holmes at Lincoln is good, too - that there has been worked for the last five year successively every winter," said my informant. "Poor Sarah Holmes! Bless her, she has saved me from walking the streets all night many a time! Some of the best of these have been in work twenty years - the Scarborough murder has full twenty years. It's called, 'THE SCARBOROUGH TRAGEDY.' I've worked it myself. It's about a noble and rich young naval officer seducing a poor clergyman's daughter. She is confined in a ditch, and destroys the child. She is taken up for it, tried, and executed. This has had a great run. It sells all round the country places, and would sell now if they had it out. Mostly all our customers is females. They are the chief dependence we have. The Scarborough Tragedy is very attractive. It draws tears to the women's eyes, to think that a poor clergyman's daughter, who is remarkably beautiful, should murder her own child; it's very touching to every feeling heart. There's a copy of verses with it too. Then there's the Liverpool Tragedy - that's very attractive. It's a mother murdering her own son, through gold. He had come from the East Indies, and married a rich planter's daughter. He came back to England to see his parents after an absence of thirty years. They kept a lodging-house in Liverpool for sailors; the son went there to lodge, and meant to tell his parents who he was in the morning. His mother saw the gold he had got in his boxes, and cut his throat severed his head from his body; the old man, upwards of seventy years of age holding the candle. They had put a washing-tub under the bed to catch his blood. The morning after the murder the old man's daughter calls and inquires for a young man. The old man denies that they have had any such person in the house. She says he had a mole on his arm in the shape of a strawberry. The old couple go upstairs to examine the corpse, and find they have murdered their own son, and then they both put an end to their existence. This is a deeper tragedy than the Scarborough Murder. That suits young people better; they like to hear about the young woman being seduced by the naval officer; but the mothers take more to the Liverpool Tragedy - it suits them better. Some of the 'cocks' were in existence," he says, "before ever I was born or thought of." The "Great and important battle between the two young ladies of fortune" is what he calls a ripper. "I should like to have that there put down correct," he says, " cause I've taken a tidy lot of money out of it."

My informant, who had been upwards of twenty years in the running patter line, tells me that he commenced his career with the "Last Dying Speech and Full Confession of William Corder." He was sixteen years of age, and had run away from his parents. "I worked that there," he says, "down in the very town (at Bury) where he was executed. I got a whole hatful of halfpence at that. Why, I wouldn't even give 'em seven for sixpence - no, that I wouldn't. A gentleman's servant come out, and wanted half a dozen for his master, and one for himself in, and I wouldn't let him have no such thing. We often sells more than that at once. Why, I sold six at one go to the railway clerks at Norwich, about the Manning affair, only a fortnight back. But Steinburgh's little job - you know, he murdered his wife and family, and committed suicide after - that sold as well as any 'die.' Pegsworth was an out-an-out lot. I did tremendous with him, because it happened in London, down Ratcliff-highway - that's a splendid quarter for working - there's plenty of feelings; but, bless you, some places you go to you can't move no how - they've hearts like paving-stones. They wouldn't have the papers if you'd give them to 'em - especially when they knows you. Greenacre didn't sell so well as might have been expected, for such a diabolical out-and-out crime as he committed; but you see, he came close after Pegsworth, and that took the beauty off him. Two murderers together is never no good to nobody. Why, there was Wilson Gleeson, as great a villain as ever lived - went and murdered a whole family at noon-day; but Rush coopered him - and likewise that girl at Bristol - made it no draw to anyone. Dan'el Good, though, was a firstrater; and would have been much better if it hadn't been for that there Madame Toosow. You see. she went down to Roehampton, and guv £2 for the werry clogs as he used to wash his master's carriage in; so, in course, when the harrystocracy could go and see the real things - the werry identical clogs - in the Chamber of Orrors, why, the people wouldn't look at our authentic portraits of the fiend in human form. Hocker wasn't any particular great shakes. There was a deal expected from him, but he didn't turn out well. Courvoisier was much better - he sold werry well; but nothing to Blakesley. Why, I worked him for six weeks. The wife of the murdered man kept the King's Head that he was landlord on open on the morning of the execution, and the place was like a fair. I even went and sold papers outside the door myself. I thought if she war'nt ashamed, why should I be? After that we had a fine 'fake' - that was the fire of the Tower of London - it sold rattling. Why, we had about forty apprehended for that - first we said two soldiers was taken ip that couldn't obtain their discharge; and then we declared it was a well-known sporting nobleman who did it for a spree. The boy Jones in the Palace wasn't much more of an affair for the running patterer; the ballad-singers - or street screamers, as we calls 'em - had the pull out of that. The patter wouldn't take; they had read it all in the newspapers before. Oxford, and Francis and Bean were a little better, but nothing to crack about. The people doesn't care about such things as them. There's nothing beats a stunning good murder after all.

Why, there was Rush - lived on him for a month or more. When I commenced with Rush I was 14s. in debt for rent, and in less than ten days I astonished the wise men in the East by paying my landlord all 1 owed him. Since Dan'el Good there had been little or nothing doing in the murder line - no one could cap him - till Rush turned up a regular trump for us. Why, I went down to Norwich expressly to work the execution. I worked my way down there with 'a sorrowful lamentation' of his own composing, which I'd got written by the blind man, expressly for the occasion. On the morning of the execution we beat all the regular newspapers out of the field; for we had the full, true, and particular account down, you see. by our own express, and that can beat anything that ever they can publish; for we gets it printed several days afore it comes off, and goes and stands with it right under the drop; and many's the penny I've turned away when I've been asked for an account of the whole business before it happened. So you see, for herly and correct hinformation, we can beat the Sun - aye, or the Moon either, for the matter of that. Irish Jem, the Ambassador, never goes to bed but he blesses Rush, the farmer; and many's the time he's told me we should never have such another windfall as that. But I told him not to despair; 'there's a good time coming, boys,' says I; and sure enough, up comes the Bermondsey tragedy. We might have done very well, indeed, out of the Mannings, but there was too many examinations for it to be any great account to us. I've been away with the Mannings in the country ever since. I've been through Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, and Suffolk, along with George Frederick Manning and his wife - travelled from 800 to 1,000 miles with 'em; but I could have done much better if I had stopped in London. Every day I was anxiously looking for a confession from Mrs. Manning. All I wanted was for her to clear her conscience afore she left this here whale of tears (that's what I always calls it in the patter); and when I read in the papers (mind, they was none of my own) that her last words on the brink of eternity was, 'I've nothing to say to you, Mr. Rowe, but to thank you for your kindness,' I guv her up entirely - had completely done with her. In course the public looks to us for the last words of all monsters in human form; and as for Mrs. Manning's, they were not worth the printing. The papers are paid for," continued the man, "according to their size. The quarter-sheets are 3d. a quire of twenty-six, half-sheets are 6d., whole sheets 1s. Those that are illustrated are 2d. more per quire than those that are plain. The books - which never exceed eight pages (unless ordered) - are 4s. a gross. The long-songs are 1s. per quire, and they are so arranged that a single sheet may be cut into three. The song-books are all prices, from 3d. a dozen up to 8d. a dozen, and the latter price alone is demanded for Henry Russell's pieces. The papers and books are sold at ½d. or ld. each, according to the locality. The average earnings of the class are, taking dull and brisk, about 10s. The best hand can make 12s. a week through the whole year, but to do this he must be a "general man," ready to turn his hands to the whole of the branches. If a murder is up, he must work either a "cock" or a conundrum book, or almanacs, according to the season; and when the time for these is past, he must take either to "Sarah Simple" ("she that lived upon the raw potato peelings," says my informant), or the highly amusing legend of the "Fish and the Ring at Stepney;" or else he must work "Anselmo; or the Accursed Hand."

Henry Mayhew, Letter to the Morning Chronicle, 7 December 1849